IV.

IRONMAKING

THE

SIXTEENTH CENTURY

It may be true to say

that the iron industry which was established in Glamorgan and Monmouthshire

during the second half of the sixteenth mtury, was the first in Wales to be

financed from capital, as we know today, with the profit motive in mind.

Ironmasters, who had already een concerned with ironmaking for this reason in

Sussex, moved to the alleys of the Taff and the Cynon in Glamorgan after

certain official ‑strictions were placed on their operations, and those

of others, in the Veald of south eastern England; these restrictions were

really directed t preventing the consumption of timber for making charcoal, the

fuel ien used in the smelting of iron. It has long been said that the timber

,as needed for shipbuilding in naval yards, in view of the sea battles gainst

Spain, but it has also been argued that the cordwood used in charcoal‑making

was not suitable for shipbuilding.

The

valleys, which the Sussex ironmasters chose to exploit in Glamorgan, were well‑wooded

and promised ample supplies of charcoal iel; they were also well‑endowed

with rivers and streams, which produced the water for driving the waterwheels,

which operated the crude ellows providing the blast for heating the fuel used

in smelting. In addition, iron ore was easily worked from outcrops and shallow

pits.

Between

1564 and 1600113 blast furnaces and forges appeared in the Taff

Valley near Tongwynlais (sward near the white brook) at Pentyrch (boar head),

Pontygwaith (work bridge), Pont‑y‑Rhun (Rhun's bridge), Dyffryn

(vale), and Blaencanaid (head water of river Canaid, white); remains of the

furnace at Pont‑y‑Rhun were to be seen on the western bank of the

Taff in 1874.96 In the

Cynon Valley a furnace was established at Cwmaman (Aman valley), at another

site called Dyffryn, with a forge

a little way downstream and another forge at Llanwonno church of Gwynno) to the

south west. A second Pontygwaith in the Rhondda Fach (little Rhondda, noisy

one) has also been mentioned as a last furnace location. The furnace ‑

the Taff furnace ‑ near Tongwyn,is supplied iron to a forge at Rhyd‑y‑Gwern

(alder ford). Sir Robert Sidney, afterwards the Earl of Leicester, 'an

experienced industrialist ad ironmasterl’ 82 set up ironworks at

Llanhari (church of St. Hari), Llantrisant (church of the three saints) and at

Angelton and Coity to the north of Bridgend.

Similar conditions

favourable to ironmaking, obtained in Monmouthshire, in the valleys of the Afon

Lwyd (grey river), the Rivers Ebbw and Usk. Ironmaking, on an extensive scale,

in the county, started a few years later than in Glamorgan and became

concentrated in and around Pontypool. The importance of water power may be seen

in the names of some of the locations which developed furnaces; for example,

Cwmffrwdoer (valley of the cold stream) 1570, Trosnant (cross brook) 1576 and

Pontypool itself (bridge of the pool).

Foremost

among the works developed in Monmouthshire at this time, were the Tintern

Wireworks, and the leading personality was Richard Hanbury, a native of

Worcestershire. He was sufficiently astute to acquire much of the woodlands of

the river valleys, which gave him control over fuel resources, and led to his

becoming a partner in the Tintern works and the proprietor of other ironworks

in Monmouthshire, in addition to those at Abercarn (mouth of the river Carn)

and Monkswood.

The

picture, which has emerged, is of an industry composed of a number of small

units, scattered throughout the two counties. Its dependence upon charcoal, and

the difficulty in maintaining adequate supplies of this fuel, made it necessary

to locate the works at considerable distances apart and in well‑wooded

districts. The works were committed to their chosen locations by the 'tyranny

of wood and water."80

Despite

this, the iron industry in Glamorgan and Monmouthshire flourished sufficiently

to develop an export trade, the finished iron being sent from the ports of

Cardiff and Newport to the midland counties of England, to Bristol and its

hinterland, to the western counties of Wales, to Ireland and to the Low

Countries. Records in the Welsh Port Books 99 show that consignments

of 'Welsh iron' were exported from Cardiff on a number of occasions between

1586 and 1601, to Bridgwater, Bristol and Flushing and that Edmund Mathew, the

proprietor of the Pentyrch Ironworks was exporting from Cardiff to London,

'pieces of ordinances', called 'sakers' and 'mynions', a trade which was not

strictly legal at the time.

The ruins

of 16th century ironmaking blast furnaces may be seen at Cwmaman, Blaencanaid

and Angelton. A blast furnace is a tall structure fed at the top with raw

materials and continuously producing metal in a liquid form, which, at the

bottom, is tapped from time to time. It has been used, according to this

principle, but in developing forms, from the 16th century until the present

day.

The

furnace at Cwmaman (ST 004992) was described by William Llewellin as a

sixteenth century blast furnace built of sandstone and lined with the same

material.101 He wrote of evidence of the existence of a waterwheel,

the furnace having been built near the confluence of two streams, and gave

details of the dimensions of the furnace in plan and section.

An

interesting detail on the Cwmaman furnace is contained in a history published

in 187597; it was, supposedly, built by three brothers who followed

respectively, the trades of stonemason, blacksmith and wood turner. The blast

for the furnace was provided by two men, each operating 'a blacksmith's

bellows', but, 'the works did not respond to the cost' and the venture was

abandoned.

The

stonemason and blacksmith left Cwmaman, but the wood turner remained to carry

on with his original trade and to make chairs of distinctive designs, which

achieved local fame. A number of the chairs survived into the nineteenth

century, the owner of one of them, in 1830, composing an 'englyn', an

alliterative stanza, to it, which contained a line claiming that the chair was

more than 300 years old. The deduction then reached was that the Cwmaman

furnace was built about 1520.

The

present-day remains are deteriorating rapidly, but illustrate the principle

adopted in the early days of blast furnace building, that of building the

structure into the slope of the ground, so that the mouth of the furnace and

the charging platform were at a higher ground level, thus making it easier to

put in the raw materials. The sandstone lining is still to be seen in a right

angled fragment of the interior of the furnace about 3 feet high.

The

blast furnace which operated at Blaencanaid (so 035042) has been

described as one which was 'simple to a degree'.118 It was situated

in a natural hollow at 900o feet on the western side of the Taff Valley. It

provides an admirable example of using sloping ground, on the west side of the

hollow, to make for easy charging of raw materials. A stream flows into the

hollow, and at a point behind the furnace and to the north of it, forms a

waterfall 8 feet high. It passes the side of the furnace at a distance of 20

feet and long, flat, inclined stones lying on the bed of the stream suggest

that they were placed there to increase the flow of water, possibly to drive a

waterwheel, which operated the bellows providing the furnace with its

air-blast.

It

was a very small furnace, sandstone-built, probably from the stone of a nearby

outcrop; the stones, in the lower levels, or near the base of the furnace, are

nearly 3 feet long and generally 3 inches thick. Most of the stonework has

collapsed; only a height of about 3 feet 6 inches remains at the front of the

furnace, which measures 9 feet across (Plate 32). The present height of the

remains of the back wall of the furnace is 8 feet and it is probable that the

original overall height of the structure was no more than 12 feet. The length

of each side wall is calculated at about 12 feet, but excavation is necessary

to determine the exact penetration into the slope of the bank. The front

aperture of the furnace is 3 feet high and 1 foot 6 inches wide and 3 feet

long, the side walls of the aperture tapering inwards towards the tap-hole and

the hearth stone. The roof of this aperture, which sloped downwards towards the

tap hole, has collapsed and the opening into the furnace at this point, is now

very irregular in shape. The bottom of the furnace hearth has a diameter of 1

foot 9 inches the lining tapering outwards to a diameter of 4 feet at a height

of 6 feet from the bottom; this was the widest point of the furnace.

Plate 32

Blaencanaid Blast Furnace Remains

A

limited excavation of the site in July 1965, by D. M. Evans of the Department

of Archaeology, University College, Cardiff, revealed the existence of a

charging platform (Plate 33) and a short length of side wall built outwards

from the northern side of the furnace. The existence of this wall, and the

discovery of a number of flagstones in the ground fronting on to the furnace,

suggest that a roofed building of some kind had been built in front of the

furnace. The area immediately in front of a furnace of this period, was the

casting floor, which was often housed in a simple building.

Plate 33 Blaencanaid

blast furnace charging platform.

A

little way downstream from the furnace, there are the remains of two stone

buildings, one on each bank of the stream, and on the southern edge of the

hollow there is an entrance to a small coal level. Unfortunately, the thickness

of the natural growth makes it impossible to form any conclusion on the significance

of the ruins of these buildings.

Nothing

is known of the ownership of this furnace. It may have been worked in

association with the furnace established at Pont-y-Rhun, a mile farther down

the Taff Valley.

Another

sixteenth century site which merits attention is that of the Angelton or Coity

blast furnace (SS 905821), near Bridgend in Glamorgan.

‘Near

the left bank (of the river Ogmore) on the windward, westerly, side of the

hill, denoting its early date, prior to utilisation of the artificial air blast,

stand the serried ruins of a blast furnace. Entwined in the interstices of its

sandstone blocks grow the fibrous roots of a sycamore tree, rearing its head

skywards in all the beauty of its brilliant foliage, but year by year bringing

by disintegration of its masonry, destruction to this interesting memento of an

ancient industry.’111

In

the article which contained these words, the height of the furnace remains at

the time, was given as 12 feet with a hearth 61 feet square, the furnace stack

tapering to a measurement of 3 feet by 3 feet at the top. An accompanying

drawing suggests an original height of 18 feet the outside measurements being

18 feet square at the base, and 16 feet square at the top, inward ledges at

heights of 9 feet and 13 feet effecting the reduction.

A

contemporary contributor to a newspaper, is also quoted as saying that when he

visited the site many years previously, the hearth of the Angelton furnace was

intact - 'it was a square hearth, not round as they are now made ... in the slag

heap I found pieces of charcoal but no coke or coal from which fact I concluded

they used as fuel charcoal only'.

The

present remains (Plate 34) show very clearly the shape of the inside of the

furnace, but it has disintegrated considerably since 1896.

Plate 34 Angelton blast

furnace remains.

An

interesting feature is the furnace interior, or lining, which was built of

tiled stone blocks if inches thick. For some reason this kind of structure led

to the conclusion that the Angelton furnace was Roman in origin, but this

cannot be sustained.

It

has been claimed82 that the furnace was built by Sir Robert Sidney,

a son of Sir William Sidney of Sussex and brother to Sir Phillip Sidney, after

he had leased land in the area for, '. . . the power to build a work for

melting, making and casting iron sows, to make iron by forge and furnace or

other means'. His interests in ironmaking in Glamorgan were extended to other

districts and a site near Coity village (ss 928827) may well have been

established by him. The excavation of this site could reveal the remains of the

hearth of an early blast furnace.

An

ironworks, which was probably established late in the sixteenth century, and

with others survived until its partial demolition by Oliver Cromwell's troops

about the middle of the seventeenth century,101 was located at

Pontygwaith (ST 079979) in the valley of the river Taff. There are no obvious

surface remains on the site but a water-colour, said to be a copy of the

original, reputedly of the Pontygwaith furnace is preserved in

the borough library at Merthyr Tydfil.

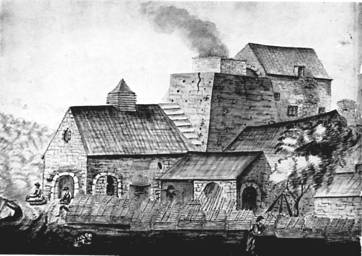

A

photograph (Plate 35) of this painting provides a very good example of the

integration of buildings achieved in an early ironworks. Towards the top

(right) is seen a tram, loaded with raw materials, about to enter the charge

house, at which level the materials would have been charged into the furnace.

To the right of the small, square furnace stands a building which probably

housed the bellows, which provided the the blast for the furnace; the bellows

were usually operated by a waterwheel. The cast house, into which the molten

iron flowed, abuts on to the front wall of the furnace; it has roof and wall

ventilation. The piled material at the front may have been pig iron.

Plate 35 Pontygwaith Iron

Works.

(ii) THE SEVENTEENTH CENTURY

During

the years after 1600 the export of iron was considerably curtailed, following

competitive production in other regions, notably the Forest of Dean, and a

number of the sixteenth century ironworks succumbed. Some of them, because of

ownership, became involved in the politics of the seventeenth century and were

partially destroyed by Cromwell's troops. It was also to be expected that some

would cease to function following the scarcity of charcoal fuel, due to the

rapid deforestation which had taken place, and to the fact that no attempts

were made to replenish the natural supply by planting coppices. As the

seventeenth century advanced, therefore, the ironworks of South Wales became

fewer in number and were, accordingly, more scattered.

In

Glamorgan a furnace was established at Caerphilly in 1680 and the works at

Pentyrch continued to operate; in Carmarthenshire the Cydweli (territory of

Cadwal) furnace came into being and in Breconshire ironmaking was carried on

during the seventeenth century at Ynyscedwyn (Cedwyn's watermeadow) and

Llanelly (church of St. Elli). In Monmouthshire the works at Tintern were

operating and two furnaces, at least, one near Llandogo (church of St.

Euddogwy) the other near Trellech (great stone), were built to provide the

works with iron.

The

sites at Llandogo, Trellech, Llanelly and Caerphilly still provide physical

evidence of iron making during the seventeenth century when charcoal was still

used as the fuel.

The

Coed Ithel (Ithel’s wood) blast furnace, near Llandogo (ST 527027) in the Wye

Valley, is sited on a hillside about 30 feet above the bed of a stream and on a

level area, contained by stout retaining walls, one of which runs parallel with

the roadway. The stream flows regularly throughout the year.

Excavation

has disclosed a furnace structure about 24 feet square.116 The

present maximum height from the foundation level is about 20 feet; the furnace

never exceeded this height by more than a foot or two.

The

square shaft was made up of 3 inches thick grey sandstone and the circular

hearth was built up from the bottom with 6 inches of white sandstone. It joined

the shaft at a point more than half way up the interior of the furnace. The hole

which took the nozzle of the bellows, that provided the blast, was about 18

inches from the bottom of the hearth of the furnace.

Among

the finds were three cast-iron runners which were probably used in the sandbeds

or pig beds, that is, the casting area, to connect the main channels, along

which the molten iron ran, into parallel furrows wherein the pigs were formed.

It

may be helpful at this stage to explain the origin of the terms 'sows' and

'pigs' in relation to iron-making.

A

sand-bed would be made to slope gently away from the furnace; it was made up of

a long main channel, running from the furnace tap hole, a number of transverse

channels in the sand, and a series of parallel furrows with their long axis

directed towards the furnace, sufficient walls of sand being left between the

furrows to form barriers strong enough to resist the pressure of the molten

metal.108 At first the lowermost of the furrows would be connected with the

main channel, communication between it and the other rows being then made in

succession, by the removal of sand barriers previously erected. The transverse

feeding channels formed the 'sows' and the parallel furrows the 'pigs'. These

names were fancifully suggested by a sow feeding her litter of pigs.

Dr.

Tylecote has concluded, that on the evidence which he obtained, the lines of

the Coed Ithel furnace are unique, although its operation appears to have been

typical of that of a mid-seventeenth century furnace in other areas. It used

iron ore from the Forest of Dean, and charcoal and bloomery cinder (slag

containing iron left on sites of early forges where iron was shaped into a

bloom or ingot), but limestone was not included in the charge.

The

furnace was in being in 1651 and between 1672 and 1676 it had an average weekly

output of 18 tons. It lasted until the beginning of the eighteenth century but

does not appear in the list of furnaces for 1717.95

The

Trellech

furnace, at Woolpitch Wood (ST 487048), is in an overgrown area with

trees growing out of the furnace ruins, but enough of the exterior remains for

it to be seen as square in shape. The furnace structure is 26 feet square at

the base and diminishes to about 20 feet square at a height of to feet from the

ground (Plate 36). It stands alongside a stream which could have provided the

power for driving a waterwheel.

Plate 36 Trellech Blast Furnace.

The

ground rises steeply from the working level of the furnace on the west side,

and there is evidence of the foundations of a bridge arch which connected the

charging platform with a roadway on level ground above. Beyond the roadway are

the remains of the walls of a building, measuring about 6o feet by 20 feet,

which was connected with operations at the furnace. It is likely that this furnace

also depended upon the Forest of Dean for iron ore, but found an abundance of

local timber, for converting into charcoal fuel for smelting.

The

third of the seventeenth century sites, where furnace remains may still be

seen, is in the southeast corner of Breconshire on the northern side of the

river Clydach in the parish of Llanelly (So 235142); there are also the remains

of an interesting building near the furnace.

The

blast furnace at Llanelly was in production during the 1600s, when it was

associated with the Hanbury family. This site must not be confused with a site

at Clydach, on the slope of a hill, to the south of the river (SO 232 128)

where, it is claimed, that a small furnace about 12 feet high was erected in

1590 and that a forge operated nearby in I600, both establishments ceasing to

exist in 16O7.113a

It

has been said that the Llanelly furnace came into being in 16o6 and a forge to

serve the furnace, within easy distance, in 1615.113a There is,

however, more direct evidence in support of its existence at the end of the

seventeenth century rather than at the beginning.

The

Llanelly furnace continued to produce until the 1860s and in its present

condition can be readily identified as a stone-built blast furnace, by the

arched passage 5 feet high and 3 feet 6 inches wide, running between the main

furnace building and the retaining wall built into the rising ground behind.

This passage can be entered from the west opening only; the opposite end of the

passage has collapsed thus limiting its length.

This

is yet another existing illustration of the practice of building a blast

furnace at the bottom of a slope, to bring the mouth of the furnace level with

the higher ground for easy charging. At Llanelly the arched roof of the passage

was in effect the under-part of a bridge arch, which connected the furnace

charging floor with the upper ground level. In this passage, in the back wall

of the furnace 2 feet from the floor there is a hole, possibly the tuyre, which

took the nozzle of the bellows which provided the furnace with its blast.

The

Llanelly furnace was built of sandstone and was 26 feet square, the retaining

wall, which contained the hillside at the back, continuing for a further 12

feet on each side of the furnace. The length of the retaining wall, which runs

from the open end of the passage, stands, but the other side has collapsed

along with the front and second side of the furnace. Extensive excavation would

be necessary to uncover details of the hearth.

On

the higher ground behind the furnace remains, there is a two storey stone

building, part ruinous and part occupied (Plate 37). This could have been the

charcoal store at one time, the 'colehous' referred to by Major John Hanbury

(who inherited the works at Llanelly and Pontypool from his father Capel

Hanbury) in his 'Observations on the Making of Iron at Pontypool and Llanelly'

dated 1704.113b The ruinous part of the building presents some

puzzling features. At the end, there is a passage with an arched roof, 8 feet

high extending from the front to the back, where it is met by another passage

which runs along the back of the building at a height of 3 feet from the

ground. This transverse passage has a similar roof to the first and is 3 feet

from its floor to its ceiling: the remains of a similar passage are also to be

seen at first floor level.

Plate 37. Ruined

buildings behind Llanelly (Brecks.) furnace.

Within

easy reach of the site there is a large dwelling-house, which may have been

built or re-built by Francis Lewis, who was the Clerk of the Llanelly Furnace

at the end of the seventeenth century and during the early years of the

eighteenth. The initials FL and the date 1693 are clearly to be seen along the

bottom of the coat-of-arms above the entrance to the house. A boundary wall,

made entirely of fairly large lumps of iron slag, runs along an adjacent

roadway for some distance.

Hanbury's

dependence upon, and respect for Lewis, are made quite clear in his

'Observations' some of which were based on Lewis's experience in making cast

iron. It is interesting to note that the production programme of the furnace

depended upon the collection and cutting of wood and its 'coling' into

charcoal.

'For

the future I think of making about 300 tun of pigs yearly at Llanelthy & I

am of opinion the best way would be to blow every year.

I

think the proper time would be to begin constantly in the beginning of

September and 300 tun would be cast in January at Farthest, so there would be

all the spring to fill the house (the charcoal store) to keep till winter &

from Sept. to the later end of Novbr. to bring the present stock.'

The

layout of the furnace area, with its coal-houses and tenements and its

proximity to Llanelly Forge, is to be seen in a survey of 1779 by John Aran.79

The furnace with its attendant charging house, cast house, and waterwheel, is

admirably illustrated in Wood's, 'Rivers of Wales'. Nothing remains in the

forge area, apart from some retaining walls and ramps but there is obvious

evidence of the existence of the forge pond.

A tinplate mill was

established on this site about 1800, the plates being made from charcoal iron

from the forge. A present-day dwelling house at the end of Forge Row, which

leads to this old industrial site, was the original tin‑house. The sheets

were liberally coated with tin, for they The works,carried a coating of 6

pounds and upwards of tin per box. 83 The works was closed in 1884

The site of

the Caerphilly furnace is to the north west of the town at T 142878, but there

are no physical remains to point to a stone blast furnace; there are, however,

slag heaps and slag is to be found in the nearby stream.

The furnace

was built in 1680,113c and was under the ownership of the Tredegar

family. 96a In 1694 the furnace was owned by John Morgan (of

Tredegar), Roger Williams and Roger Powell, the last of the three living at

Energlyn (originally 'Geneu'r Glyn') House within easy reach of the furnace. In

1787 a bigger furnace was built to replace the original and 'a powerful blowing

engine'96a was provided in place of the old bellows which were

actuated by a waterwheel.

Before the

re‑building, about 200 tons of iron were produced each year, but

afterwards 503 tons were produced in 1796. This was an appreciable production

figure at the time.

The

Caerphilly furnace was under several different ownerships – the names of

Pratt and Harford being associated with it and a well‑known lcal figure

Edward Lewis, had a share in it in 1747. The furnace remained in production

until 1819. 96a It is included in John Fuller's list of 1747 ‑

producing 200 tons; some of this iron was, during the eighteenth century,

supplied to the two forges at Machen.113c

iii)

THE EIGHTEENTH AND NINETEENTH CENTURIES

In the

preface to his book on the South Wales ironworks of the 1760 - 1840 period,

John Lloyd wrote of'. . . the introduction of a great chain of Iron Works into

South Wales in barely more than a generation, and their rapid development to a

great height of prosperity . . .'102 This was the period which gave

to South Wales its first concentration of industry within a defined area - the

northern rim of the South Wales coalfield; it was a compulsive concentration

which sprang from the easy availability of all the raw materials necessary for

the making of iron.

At the

heads of the valleys, the 'blaenau', and on the uplands beyond, iron ore was

easy to come by, '. . . worked at slight expense in patches by turning over,

like a garden, the open mountain slopes’.101a

The work of

Abraham Darby, at Coalbrookdale, had culminated in 1709 in the use of coke as a

fuel, in place of charcoal; the coal for coking was available in abundance in

the South Wales coalfield and there were adequate supplies of limestone, used

as a flux in the smelting process, and of stone for furnace building.

The blast furnace of

this period was, in essence, a vertical, circular chamber, often called, the

shaft, which 'widened from the bottom upwards and from the top downwards'.108a

The inner lining was made of re‑brick, common brick and a rubble of stone

as a filling. Externally the furnace was a solid, square structure massive in

appearance. The internal chambers varied in shapes as the period advanced, each

depending upon the theories of the furnace designers and builders.

The

furnace top was a cylindrical chimney surrounded by a platform; around the

lower part of this chimney there were, usually, four openings of regular shape

through which the furnace was charged from the platform.

The stone-built

furnaces were gradually replaced by rounded structures clad in wrought iron

plate, and with the introduction of hoists for bringing up the raw materials to

the charging platforms, the need for building furnaces into sloping ground

ceased.

At the beginning of the period, waterwheels were used to drive the bellows which provided the blast, but steam‑driven blast engines were in use at the beginning of the nineteenth century. This resulted in a great increase in efficiency and brought increased production. The blast traveled through the blast main, a cast‑iron pipe which passed round the furnace, injecting the blast into the furnace through pipes connected with the openings in the furnace walls, the tuyeres.

In

attendance upon the blast furnace were kilns in which the limestone and iron

ore were calcined, or roasted to eliminate moisture and impurities, before the

smelting process in the blast furnace. At the front of the furnaces there were

cast houses, and always nearby, the engine houses which contained the blast‑producing

engines.

The

process of conversion of the cast iron into malleable or wrought iron, was

carried on in buildings which housed the puddling furnaces in which the

conversion was carried out. As the period advanced, rolling mills for the

production of bar iron were developed and each ironworks' site was clustered

with many buildings.

Many of

the works, which were established on the strip of land extending from Blaenavon

(headwater of the river Afan) to Hirwaun (long moor), began to run down about

one hundred years ago. It is surprising that so much structural evidence of the

works remains at the end of that period. Amongst it there are a number of

interesting features ‑ one would expect it to be a rich field of study ‑

some of which lead to related features and sub ects, of which mention must also

be made.

The

approach to the industrial archaeology of the period of the ironworks must be

selective as far as possible, to avoid needless repetition, and a geographical

approach, starting on the eastern side, may be better than one based upon the

chronology of the ironworks, which could lead to bewildering movements to and

from different parts of the area.

MONMOUTHSHIRE

The

ironworks at Blaenavon dated from 1789 in which year a lease was granted by the

Earl of Abergavenny to Thomas Hill of Stafford and his associates Thomas

Hopkins and Benjamin Pratt. There is, today, clear evidence in the towering,

disintegrating masonry, of the original blast furnaces clinging to the

hillside. Of all the blast furnace remains still to be seen on the sites of old

works, these at Blacnavon present the classic example of using the upper levels

of the ground for charging the furnaces (Plate 38)

Plate 38 Remains of

furnaces Blaenavon.

The

furnaces were described by Archdeacon Coxe in 180184 as. . the

buildings which are constructed in the excavations of the rocks . . .' In this

book there is an engraving of the Blaenavon Ironworks in 1799 which indicated

that three furnaces were in operation and that each one was connected with a

charging house, above and behind, and a cast house in front and on ground

level. It shows also, some tramroads and the horses and trams which operated on

them.

A

plan of the Blacnavon works dated 1814 and preserved at the National Coal Board

survey office on the site, gives a number of interesting details. It shows the

five furnaces as two pairs and a single furnace this is seen in the present

ruins. There were coke yards and 'the Mine Kilns' behind the furnaces on the

charging level. The tram roads to 'mine works' and 'limestone rock' are shown

and other features included, are 'mouths of levels for getting coals', 'mouths

of levels for getting Mine or Iron Ore', a new and an old blowing engine, two melting

fineries and cinder heaps.

A

map of 1819, preserved at the Monmouthshire County Record Office, shows that

there were five furnaces in blast; they were still in production in 1839.105

Among the remains, the round shape of a furnace stack is prominent, revealing a

number of brick courses, and the stone masonry of the outside walls of another

furnace is also to be seen. The disintegration has also revealed the use made

of wrought iron bands and keys, as reinforcement during the building of the

furnaces.

The

outside walls and gable ends of a number of cast houses have survived, as have

the remains of an engine house stack. Another interesting feature on the site,

is what remains of a water balance tower erected near a coal level which was

driven to the south cast of the line of furnaces.

In

1817 the Blaenavon works became associated with a

works built at Garnddyrys (bramble cairn) on the western slopes of the Blorenge

mountain. Cast iron was sent to this works from Blaenavon for finishing; the

sites were connected by a tramroad. The Blaenavon works was connected by

tramroad to the terminal of the Monmouthshire Canal at Crumlin (originally

'Crymlyn', curved lake) and the Garneldyrys works was similarly joined to the

Brecon and Abergavenny Canal at Llanfoist (church of St. Ffwyst); from the two

works, between 1802 and 1840, 447,392 tons of iron were transported to Newport.114

This was in the form of pig iron and cast iron and finished iron such as

puddled bars, rods and rails.

The

Garnddyrys works was closed in i86o and by 187o Blaenavon had ceased to produce

iron rails -this applied to all ironworks which could not compete with the

Bessemer steel rails which were then being produced at Ebbw Vale and Rhymney.

At

the head of the Sirhowy (Howell's land) river, stand the remains of the Sirhowy

Ironworks, which, after an indifferent start, following the granting of the

first lease of the land in 1778, was from 1794 operated jointIy102b

by William Barrow, an 'ironmaster' and the Revd. Matthew Monkhouse, Clerk, of

Sirhowy and Richard Fothergill - a name which became well known in the South

Wales iron trade - of Surrey, who had a small ironworks in the Forest of Dean.118a

In 1800 the partners were joined by Samuel Homfray of the Penydarren (top of the

hill) Ironworks and a new works, the Tredegar (Tegyr's farm) Ironworks, came

into being less than a mile downstream from the Sirhyow works, the two works

coming under the joint ownership of the new partnership. The Tredegar works, in

time, became the bigger of the two having five blast furnaces to Sirhowy's

four.

In

1818 the Sirhowy lease was up and Richard Fothergill's belief that he would

secure its renewal, led him to confide in James Harford, who had become a

partner of the Honifrays in their enterprise at Ebbw Vale in 1816. It seems

that Harford acted unethically by acquiring the lease for himself, and as his

acquisition of the Sirhowy works happened soon after the Homfray family had

given up their interest in Ebbw Vale, he became one of the most powerful

ironmasters in Monmouthshire. This led to the discontinuation of the joint

management of Sirhowy and Tredegar and Fothergill ordered the removal of all

moveable plant and rolling stock, such as engines, trams, tram-plates and

barrows to within the Tredegar area, so 'that there should be no connection,

however trifling, between the two works in future."118b

The

remains at Sirhowy are fairly typical of those of the ironworks of the period -

lofty arches, collapsed furnaces and walls gradually disappearing beneath coal

rubble. It is known that a steam engine was introduced in 1797 'to assist the

water power'118a but it seems that a waterwheel survived until the

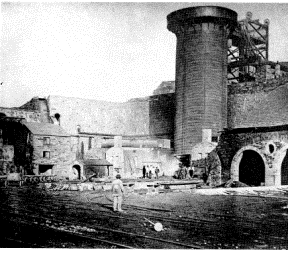

late 1870s at Sirhowy (Plate 39).

Plate 39 Sirhowy

ironworks late I870's

The

evidence, which is available in old photographs, is of considerable assistance

in giving an idea of layout, the juxtapositions of furnaces, engine houses and

other buildings and of the techniques employed in ironmaking. They also

illustrate the changes in the design and appearance of blast furnaces and

adjacent housings as the ironworks developed.

The

history of three sites at Rhymney, which were developed as ironworks, reveals

the usual agreements on leases, partnerships and the subsequent developments in

production when commercial bargaining had subsided. There is a great deal that

is interesting on the three sites today, that of the first development at Upper

Furnace, of the Union Works and of the Bute Iron Works, all three eventually

being merged into the Rhymney Iron Company. ,

The

site at Upper Furnace was first developed in 1800 as the Union Iron Company by

some Bristol merchants who were attracted to the area. A stone furnace was

built on the left bank of the River Rhymney, inside the county boundary of

Brecon. By 1802 'a considerable iron furnace had been erected and Iron Works of

considerable extent established upon the premises, and a Dwelling-House built

on the leasehold land adjoining to the furnace as a residence for the Manager,

Mr. Richard Cunningham.102c

The

ruins of the base of the furnace only remain but the topography of the site is

such that it can be recognised, by comparison with others, as one which

accommodated a small nineteenth century ironworks. The dwelling house of the

manager still stands and alongside it a warehouse-like building which bears the

date 1802 above one of its doorways.

The

Union Iron Company became a target for Richard Crawshay, Cyfarthfa Ironworks,

Merthyr Tydfil, who wished to establish a son and son-in-law in an ironworks.

He succeeded, and in 1803 the Union Iron Works Company came into being, two of

the previous proprietors being entrusted with its management. One of these,

Thomas Williams, may have been the first Welshman to have participated, as a

proprietor, in an ironmaking enterprise. This works was developed on the same

side of the river, at a point downstream where the bottom of the valley was

wider.

In

1804 it was taken over by Richard Crawshay and Company and was carried on under

the ownership of Benjamin Hall, Crawshay's son-in-law until 1820.

On

the opposite side of the river, in 1825, the Bute Iron Works was established;

three blast furnaces were erected and they 'were of a somewhat pretentious

style of architecture, having a front of Egyptian design.'102d

Within

a few years the two works were amalgamated into the Rhymney Iron Company, a

concern which for many years afterwards was a prominent industrial name, first

in ironmaking and subsequently in coal-mining and marketing.

The

site of the Rhymney Iron Company has yielded some interesting industrial

remains. Until a few years ago there was some evidence of the fanciful style of

the blast furnaces on the tight bank of the river. It is of interest to refer

to the furnace built by John Bedford at Cefn Cribwr (comb ridge) about forty

years earlier, described on Page 78, and his inclusion of a 'Ballustrated.

Battlement Level with the Bridgehouse floor'.

The

interior of one of the Rhymney furnaces may still be viewed from above, and part

of one of the bridge arches - these spanned the distance between the charging

platforms and the level ground beyond remains. The bridges themselves, however,

are all in a collapsed state.

At

the northern end of the works site, there are the remains of batteries of coke

ovens, each oven being of the long rectangular type, which had no provision for

the utilisation of the gas given off, for heating purposes in smelting and

other processes in the works. An ironstone level, on this site was penetrated

for a distance of about seventy-five yards in February 1966 by members of the

mining and metallurgy section of the South East Wales Industrial Archaeology

Society and a small, wooden tram

was found about thirty yards from the level mouth, completely submerged

in water but standing on rails. The level is about six feet high and six feet

wide with a semicircular arched roof and masonry lining. The rail track was on

a raised portion with drainage channels on either side, the rails themselves of

cast iron right-angle plates, the tram wheels being without flanges. A small

amount of ironstone pins and nodules, were removed from the tram before its

recovery.

The

body of the tram measures 4 feet 3 inches long by 1 foot 6 inches high by 1

foot 3 inches wide and it carries strengthening straps of wrought iron around

the sides and bottom. One end was open for loading and unloading, the inside of

the panel at the other end bearing an indentation, consistent with contact from

a shovel during the removal of ironstone. The wood of the tram seems to be

birch.

NORTH

GLAMORGAN

It

could be claimed that the story of the iron industry in Merthyr Tydfil (church

of St. Tudful) during the years under review, epitomises the story of the iron

industry throughout the region. Four ironworks of great magnitude - Dowlais,

Penydarren, Plymouth and Cyfarthfa grew out of small enterprises, dependent

upon waterwheels and bellows for air blast. Physical evidence of these

ironworks in remains of furnaces and buildings, is not extensive, but a brief

look at the historical development of the works, and the height of production

achieved, is permissible if only to emphasize how quickly the evidence of a

vast industry disappears, and how limited is the time still available to the

industrial archaeologist.

The

story of Dowlais (black brook) Ironworks begins with the acquisition by Thomas

Lewis, Llanishen (church of St. Isien), of a lease of land in 1757 in Dowlass

and Tory Van and the formation in 1759 of a

partnership of nine persons with a capital of £4,000, which agreed to build a

furnace or furnaces 'for Smelting of Iron Ore or Iron Mine or Stone, into Pig

Iron'. 90

Dowlais

furnace was the second coke furnace in South Wales, the first being at Hirwaun.

It has been generally accepted that charcoal was the original fuel used in

firing this furnace, but this theory has been confidently refuted.104

Merthyr Tydfil's elevation above sea-level was not conducive to tree growth and

the original lease (which reserved all timber trees for the lessor) included an

agreement to share 'all Metals, Castings, Iron, Timber, Wood, Coal, Coak, Charcoal, Braises, Tools, Utensils.'

The fact that the

enterprise 'was a direct result of the Horseha furnaces, Shropshire which used

coke, and in 1757 were each making 15 tons of iron per week, a total of nearly

1600 tons per annum’104 lends considerable weight to this argument.

'Any statement that, after 1757, any South Wales furnace started on charcoal is

mythological', ‑ Dr. R. A. Mott, one time president, the Sheffield Trades

Historical Society and of the Coke Ovens' Managers' Association, in a letter to

the author.

John

Guest, of Broseley, near Coalbrookdale, where coke was first used successfully

in the smelting of iron by Abraham Darby in 1709, was appointed manager of the

Dowlais furnace in 1767 after a number of years at the Plymouth furnace, named

after the land owner, the Earl of Plymouth. In his early days at Dowlais the

furnace made 18 tons of iron per week using 8 tons I cwt. of coal per ton of

iron produced. 78

The

general use of coke was soon followed by other improvements in the technique of

ironmaking; blowing cylinders replaced the wood and leather bellows for

providing the blast, and the steam engine took the place of the waterwheel. Due

emphasis should be given to these technical developments, which enabled the

emergent ironmasters to take full advantage of the easy availability of the raw

materials they required; the rapid progress made would not have been possible

without the use of coke and the power of the steam engine.

In 1786

the management of the Dowlais Ironworks was taken over by Thomas Guest, son of

John Guest and by this time an annual output of 1,500 tons in 1763 had been

increased to 5,500 tons. The export of Dowlais iron to America started in 1780

In 1800

three blast furnaces were in operation and the works was developing, but it

must not be assumed that the development of the Dowlais Iron Company and other

ironmaking concerns went unimpeded.

Among the

original lessees was Isaac Wilkinson of Wrexham, who held a 1/16th share in the

venture, and who had in 1757 taken out a patent for a cylinder blower, in which

a piston was operated by a waterwheel.104 A cylinder blower of this

kind was installed on the Dowlais Brook and was referred to as an 'Engine' on a

map of July 8th, 1769, which is with the Dowlais Papers at the Glamorgan County

Record Office; the length of the pipe carrying the air from the cylinder to the

furnace appears to have been considerable. Unfortunately the Dowlais brook

could not provide a constant, adequate supply of water and a high rate of

production was not reached until a Boulton and Watt double‑acting engine

and the John Wilkinson, son of Isaac Wilkinson, cylinder blower were introduced

in 1803 ‑

In addition to technical

deficiencies, the wars of the period 1795 to 1815 brought depressions, as the

problems of over production had to be solved, and the re‑adapting of

ironmaking plants for products of peace became necessary, only to be followed

swiftly by a re‑conversion, to meet the needs of war as another outbreak

occurred. In such circumstances, a stable development was difficult and the

final magnitude reached by this and other ironworks is all the more creditable.

John

Josiah Guest assumed control of the works in 1807. By 1815 five blast furnaces

produced 15,600 tons per year and in 1823 ten furnaces produced just over

22,000 tons. In 1845 eighteen blast furnaces provided a weekly production of

101 tons of iron per furnace; six of these furnaces were included in the new

Ivor Works built to the north of the original works.

The

Dowlais Company mined coal and iron ore and produced pig iron, much of which

was sold to companies which used the iron for manufacturing purposes; for

example, Brown Lenox & Co, the chain-makers of Pontypridd and the Neath

Abbey Iron Works, where various kinds of engines were made. The Company also

refined its own iron, and iron bars were forged and rolled into rails after the

coming of the railways ‑wrought iron rails for tramroads were made in

earlier times. The rails for the Stockton and Darlington Railway, the first

passenger railway, came from Dowlais in 1821.

Wrought

iron was produced in puddling furnaces of which there were many in an ironworks

such as Dowlais. The process was invented by Henry Cort and was patented by him

in 1784

A puddling

furnace (Plate 40) had a shallow hearth, with a fire grate separated from it by

a firebrick bridge; it was formed externally of cast iron plates and provided

with suitable openings in front for the fire hole and the working door, and

lined internally with firebrick. The crown of the furnace was also lined with

firebrick, and at the end opposite to the fire grate, there was a flue

connected to a simple, rectangular stack provided with an iron damper.

Plate 40. Iron Puddling Furnace

Before the

puddling process was started, the furnace bottom was specially prepared and it

was important that it should be constantly kept in good working order.

When the

furnace was red-hot, pig iron, usually in half pigs, was fed into it with a

quantity of hammer slag. The heating of the iron went on for some twenty

minutes and the pigs were then turned to heat them more uniformly. The mass was

then stirred up with an iron bar to bring up any pieces of iron not completely

melted.

The next

stage was the puddling or rabbling of the charge with long iron bars (rabbles),

bent at the end at right angles, through a hole in the side‑wall,

exposing it evenly to the action of the flames. The iron was thus 'cleared' or

purified and then brought to the boil and became pasty, or in the language of

the puddler 'came to nature'. The pasty iron was then worked by the puddler

with his rabble, into a number of balls which were lifted from the hearth with

tongs and transferred to a hammer to be rid of the slag. This was then rolled

into 'puddled bars', the name given to crude wrought iron.

The whole operation

lasted about two hours, the work being extremely arduous and the physical

effort required to manipulate the metal in the heat, was 'the severest kind of

labour ever undertaken by man'. 87

In the mid‑forties

Dowlais Ironworks was the largest works in the world, employing 10,000 and

having in addition to the furnaces, rolling mills, forges and foundries.

The great

expanse of land once occupied by the Dowlais Ironworks is now fairly clear of

buildings. There is much rubble but the remains of the brick works are still to

be seen and those of the side walls of blast furnaces which jut out from higher

ground. All this is in marked contrast to the spectacular evidence of the works

in full production, contained in three watercolours painted by G. Childs in

1840; these are at Guest Keen Iron and Steel Works, Cardiff. One shows at least

14 of the huge blast furnaces in operation at the time; another (Plate 41)

shows in close‑up the charging platform of a furnace and the preparation

of the charge for a furnace indicating quite clearly the participation of women

in this work.

Plate 41.

Preparation of Raw Materials Dowlais Ironworks, 1840.

Among the

remains on the site are the ruins of early coke producing ovens (Plate 42).

They suggest that originally each oven was rectangular in shape and in its

horizontal section had the form of a rectangular chamber, covered with a

flattened arch. Ovens of this type were separated from each other by a

comparatively narrow brick wall.115 The width of the oven varied

from 7 feet to 8 feet and the dividing wall was between 18 inches and 3 feet in

thickness. A feature of these walls was that they were sufficiently thin to

transnmit heat from one oven to the next, so that when an oven had been

discharged and was being re‑started, the ovens on each side helped it

along by the transmission of heat.

Plate 42.

Dowlais Ironworks – Ruins of Early Coke Oven

The ovens

were charged by hand from the front and from floor level, and the gases formed,

escaped into the outside air through a hole in the roof of each oven. At the

charging end there was a lifting door made of cast iron.

The

remains of the Dowlais ovens, reveal that the thickness of the coal charged was

about 12 inches, there being a lack of carbon deposit on the lower three

courses of the brickwork interior. The present inside measurements suggest that

each coke oven was about 6 feet 6 inches wide, by 6 feet high and 12 feet 6

inches deep. They were stop‑ended or single door ovens.

The

Penydarren Ironworks was established on the left‑hand side of the Dowlais

Brook, adjoining the Dowlais Ironworks to the south. Its present day remains

are negligible, comprising only the broken remains of furnaces, clinging to the

rising ground of the small hill which gave the works its name. In Tram Road

Side, a short distance from the main site, there are also the ruins of small,

stone re‑heating furnaces, which appear to have been built in pairs, with

a chimney common to each pair.

This ironworks cannot be

dismissed summarily in view of its association with the Penydarren Tramroad and

the Cornish engineer, Richard Trevithick.

The works

came into being in 1784 under the ownership of three sons of Francis Homfray ‑

Jeremiah, Thomas and Samuel and George Forman of London. Francis Hornfray had

been invited by Anthony Bacon, some two years previously, to establish a

refinery and a forge at Cyfarthfa, the iron to be supplied by Bacon from his

own furnace there. This arrangement was discontinued when Bacon, then Member of

Parliament for Aylesbury, withheld the iron supplies, after he had negotiated

with the Government to supply cannon for the army and the navy, which were then

engaged in the American War of Independence.96b

It is

assumed that the Penydarren site was chosen by Francis Hornfray and that the

lay-out of the works was based on his experience as an ironmaster in the

Midlands; the management of the works, however, was undertaken by two of the

brothers, Jeremiah and Samuel Homfray. 'This was in 1786, or thereabouts, and

in the course of the next six or eight years a pretty little Iron‑Works,

complete in every respect, had been established close to the left bank of the

Dowlais Brook."Ole One readily accepts that a nineteenth century ironworks

merited such a description.

In common

with the other ironmasters in Merthyr, the Hornfrays were hampered by the lack

of efficient communication with the port of Cardiff. Their joint efforts

resulted in the passing of the Glamorganshire Canal Act in 1790, and by 1792

the canal was navigable from Merthyr - Cyfarthfa Ironworks - to Pontypridd, and

to the sea-lock at Cardiff on February 10, 1794. The canal has, by now, been

filled in for much of its length but at various points along its route the

ruins of locks still remain and some of the original bridges are still

standing.

The

Glamorganshire Canal did not prove to be the complete answer to the transport

problems of the ironmasters; there was constant congestion, due to the heavy

demands made upon the waterway, particularly between Merthyr and Abercynon,

where numerous locks had been built to compensate for the steep descent. This,

and a deeplying disagreement with Richard Crawshay of Cyfarthfa Ironworks, led

the partners of the Dowlais, Penydarren and Plymouth Ironworks to build a

tramroad from Merthyr to the canal basin at Abercynon. It became known as the

Penydarren Tramroad103 and it achieved fame as the tramroad on which

Richard Trevithick's locomotive drew a load on rails - the first steam

locomotive to have done so - on Tuesday, February 21st 1804, 'a date forever

memorable in the history of the locomotive.'88

In 1803

Trevithick became associated with Samuel Hornfray and the ironmaster interested

himself in Trevithick's work on high‑pressure steam engines, providing

him with the facilities to build his 'Tram Waggon' at Penydarren.

The

tramroad is not without its interest today; appreciable lengths of it reveal

parts of the stone sleepers, which carried the 3 foot lengths of cast‑iron

plate rails, which can still be recovered. The passing place at Pontygwaith (ST

081976) remains in being; a relic of the tramroad, a cast‑iron wheel, was

discovered in June 1966 by two telephone line workers, about half‑a‑mile

from this point, in the direction of Abercynon, partially buried in the side of

the embankment which drops steeply to the river Taff. This cast‑iron

wheel, 31 inches in diameter, contains eleven spokes and it is reasonable to

assume that it was part of a tram which traveled along the tramroad at one

time.

Trevithick's

locomotive was not a complete success because its great weight caused the iron

tram-plates to break; it was ultimately converted into a stationary engine and

used as a prime mover at the ironworks.

The

Plymouth Ironworks, the second to have been established in the Merthyr area,

followed upon the granting of a lease of land by the Earl of Plymouth to Isaac

Wilkinson of Wrexham, and John Guest of Broseley (associated with Dowlais from

1767) in December 1763, who, to quote from the lease, intended 'to erect ...

certain ffurnaces, fforges, Mills, pothouses, or other Works for the making and

Manufacturing of Iron'. From the outset the works bore the name of the

landowner, the first occupiers styling themselves as 'Messrs. Wilkinson and

Guest, Plimouth Company',102f but for some time the works bore the

name of 'Ffwrnes Isaf', the lower furnace, its original location being given as

Coedcae Glynmil (quickset hedge of mill). 96c

In common

with many of the ironworks of South Wales, the story of the beginnings of the

Plymouth Ironworks has a strange fascination, but it will be enough to mention

that Anthony Bacon already had an interest in 1766 ‑ he was thinking of

buying more shares in the venture in June of that year122 and his

Cyfarthfa Company became the owners by the end of 1766 ‑ and that his

brother‑in‑law Richard Hill took over the management in 1784 and

subsequently acquired the works which remained in the possession of the Hill

family until 1862.

This

works, although possibly overshadowed by the other works at Merthyr Tydfil, was

not unimportant. On the original site two more furnaces were producing by 1800

and a fourth in 1815 ‑ the remains of one of these may still be seen at

SO 059049, much of the surrounding area being recognisable as the site of the

ironworks.

In 1807

the Plymouth Forge Company established a forge at Pentrebach (little village)

(SO 06204I), which was followed by a rolling mill in 1841. A short distance to

the south, at Dyffryn, a blast furnace was erected in 1819 and followed by two

others and a blowing engine and a battery of coke ovens by 1824. A plan of the

Dyffryn Furnaces drawn in 1861 (a copy of which has been deposited in the

Department of Industry, National Museum of Wales) shows five blast furnaces,

numbered 5, 6, 7, 8 and 10, kilns and limestone sheds, a refinery, cast house,

engine houses, a double‑waterwheel and a 'fitting‑up' shop.

The

remains of the blast furnaces have been slowly covered by coal refuse tipping,

a rough half section of one only still standing, the wall of which is slowly

disintegrating.

Anthony

Hill, son of Richard Hill, emerged as an important member of this Company.

Regarded as one of the leading chemists and metallurgists of the day he was

responsible for a number of experiments aimed at improvements in ironmaking.

During his time the iron produced by the Plymouth Iron Company was ten

shillings higher in price than any other iron 'because it was of better

quality.’96d

The fourth

of Merthyr's ironworks was the Cyfarthfa (barking place, where animals stand at

bay) Ironworks inevitably linked with the Crawshay family. The main works

covered an extensive area on each side of the river Taff, on the north‑western

outskirts of Merthyr and a subsidiary, the Ynysfach (little island) Ironworks

was developed on the right hand bank of the river, west of the centre of the

town.

The

accounts of the origins of this vast enterprise - 'Cyfarthfa works were by 1807

the largest ironworks in the world, with six furnaces making over 10,000 tons

per annum' - are fairly consistent. In a flourish of hyperbole, Charles Wilkins118c

states that the first furnace at Cyfarthfa was built in 1765; John Lloyd102g

accepts this date and locates it as being 'some little distance higher up the

river than the present main works. This No. 5 has a plate on it dated 1765, W.C

(William Crawshay) 1827, and is one of the sights of Merthyr'; in 'Hanes

Morgannwg'96C the date is also given as 1765 and the location as near

the confluence of the two Taff rivers, Taf Fawr (great river Taff) and Taf

Fechan (little river Taff).

The

Charles Wood Diary122, however, reveals that the first furnace was

built in 1766/67 by Wood himself for Anthony Bacon and Company, in which Wood was

a partner. Charles Wood was the son of William Wood, an ironmaster of

Wolverhampton and entries in his diary in 1766 and 1767 give numerous details,

relating to the building of the Cyfarthfa furnace and forge building, and of

the association with the Plymouth Ironworks.

A forge,

taking pig iron from the Plymouth furnace, had already been built and Wood,

whilst the furnace was being built, was adding other buildings on the forging

site. By this time, the Plymouth furnace had been acquired by Bacon and many of

the castings for the Cyfarthfa furnace were being made there.

Unfortunately

the Diary does not give the exact location of the furnace; there are constant

references to the farms of Llwyncelyn (holly grove) and Rhyd‑y‑Car

(vehicle ford) at present districts of Merthyr Tydfil, but there is nothing

conclusive about either of these. It may be that the location given in 'Hanes

Morgannwg' is the right one, because Wood refers to the farm called 'Tai Mawr'

(big houses), known to be immediately to the west of Taf Fawr and a little

above its confluence with Taf Fechan. On the other hand, immediately below the

confluence of the two rivers, on the right bank of the Taff, are to be found

the remains of the circular hearth of an early furnace (Plate 43) and there is

a substantial depth of water in the river at this point, but it cannot be

argued with certainty that this was the original site.

Plate 43. Cyfarthfa

Ironworks Early Furnace Remains

It must be

accepted that the site was fairly close to the main river, in the light of the

entry in Wood's Diary for September 9th 1766. 'Leveled the Bank, against which,

the furnace is proposed to be built; it is 47 feet high to the flat part of the

field, & from thence to the surface of water (about 6 inches running over

the Wear) 19 feet more, in the whole 66 feet. The stack may be 50 feet high,

the foundation 6 feet and then there will remain 10 feet for the Cistern &

cut, or back race, for a flat bottom boat to convey the metal to the

flourishing furnace etc. It may be contrived, for the metal to be put into the

Boat, out of the Cistern, which will save room for binns & Labour, in

taking it out of the Binns. This may be considered of.'

The

reference to the 'Cistern' and the conveyance of the metal to the 'flourishing

furnace' is mystifying.

This entry

also contains a reference to an agreement for raising of imine' (ironstone)

from Penywain (end of the moorland) which was due west of Tai Mawr and not far

distant.

Wood also mentioned the building of a furnace stack, 36 feet square and 50 feet high and 'the Holme where the Blast‑furnace is proposed to be erected' is described as a 'very convenient place, a fine bank for an high one and if there should not be found room for a bridge-house (this could mean a charging house) at the back of the Stack, an Arch may be sprung to the Rock upon the Bank . . .' In this entry, which was for June 22nd 1766, there follows the significant phrase, 'The bank for coking the coal will be inconvenient . . ‘, which makes it fairly certain that the Cyfarthfa furnace used coke from its first operations. This view is strengthened by a further entry, dated June 25th, when Wood showed the site of the proposed blast furnace to Isaac Wilkinson (of Dowlais and Plymouth) 'which he much approves of but advises to take the field on the other side of the road, for a Bank to burn Stone and Coke Coal.'

The widespread remains

of kilns, blast furnaces and various kinds of buildings, long lengths of

retaining walls and enormous slag heaps, suggest that the Cyfarthfa Ironworks

at the height of its production, covered a large area of land to the west of

the Taff. There are photographs and paintings which show this to be so.102h

The most interesting of the remains are those of the Ynysfach Furnaces

a short distance to the south of the main works. There are four furnace

structures, but all the front arches have been bricked in and the stacks have

collapsed inwards at a height of about 20 feet. It is still possible, however,

to walk the length of the arched passage, which ran beneath the bridge house

and which stood on the same level as the charging platforms of the furnaces; it

is fairly certain that this passage carried a blast pipe from one of the two

engine houses (Plate 44) ‑ even in its ruined state an impressive building

‑ which stood at the end of the line of furnaces and is seen in the

background of a photograph of the site, taken in 1905.102g This

engine house, and the second, had stacks in attendance and there were cast

houses in front of the furnaces; beyond the cast houses stood the refinery.

Plate 44. Engine House Serving Ynysfach Furnaces

One of the

photographs of these furnaces shows a cast iron key plate bearing the initials

'C & G' and the date 1801.102g Two furnaces were built as a pair

in 1801 by Richard Crawshay, who bought the Works from Anthony Bacon's heir in

1794, and Watkin George, 'the mechanical genius of Cyfarthfa' 118d

who became a partner in the company in 1792. The cast iron bridge (Plate 45)

which spanned the Taff to the east of Ynysfach, was designed and built by

Watkin George in 1800 of an iron reputed to be rustless; this bridge was

unnecessarily removed in 1964.

Plate 45. Cast

Iron Bridge Merthyr Tydfil

Another

key plate still remains at Ynysfach, in the arch of the third furnace; it bears

the date 1836 and the initials of William Crawshay II, who became the sole

owner of the Cyfarthfa Ironworks in 1834, and probably indicates the date of

the building of the remaining two of the four furnaces.

Ironworks

were established at Abernant (mouth of the brook) immediately to the north‑west

of Aberdare, in 1802, by Jeremiah Homfray and his partners and came under the

direction of Rowland Fothergill in 1819, when they were grouped with the

Aberdare Ironworks under the title of the Aberdare Iron Company. Chancery

proceedings in 1846 brought forth a list of Particulars referring to a proposed

sale of both works; a copy of this list, dated 11th June 1846, is available at

the Cardiff Central Reference Library.

On the

site at Abernant there are at present only the remains of a blast furnace,

which has crumbled almost to the top of the arch above the fore‑hearth,

and a chimney stack which served an adjacent enginehouse. A photograph of the

site about 50 years ago, which has happily been preserved, shows a blast

furnace standing to three‑quarters of its original size, yet in a ruined

state, with a three‑storeyed engine house, and its attendant chimney

stack, a very short distance away from it. Between the furnace and the engine

house, there is an air reservoir or regulator, which regulated the blast

provided for the furnace by the engine. The air reservoirs in use at ironworks

in South Wales were reputed to be spheres made of iron plates ‑ the one

in use at Penydarren Ironworks, Merthyr between 1825 and 1850 is known to be

spherical ‑ but the reservoir at Abernant is seen (Plate 46) to be

ellipsoidal and located in an upright position. The blast main leading from the

base of the reservoir into the side of the furnace is plainly to be seen. This

photograph provides rare evidence of the use of a regulator at a South Wales

ironworks during the first half of the nineteenth century.

Plate 46. Abernant Ironworks

The sale particulars of

1846 indicate that there were at Aberriant three blast furnaces, fineries,

three blowing‑engines, water‑wheels, forges and rolling mills 'with

engine power complete' and 'blast and other pipes in use and regulators in

use'. The particulars also include the important information that one of the

blast furnaces 'has hot air apparatus in full work', and another the same

apparatus, 'but not in a state quite fit for present use'. This indicates that

hot blast was used in smelting iron at Abernant at least before 1846. The

introduction of hot blast is credited to James Beaumont Neilson in 1828, when

it was used at the Clyde Ironworks; James Budd first used it in South Wales ‑at

the Ystalyfera Ironworks in 1844

The first

blast furnace in South Wales to use coke as fuel,104 was the Hirwaun

furnace established in 1757 by John Maybery who had operated a forge at Powicke

in Worcestershire. The coal used was anthracite.

The

ironworks which was developed on this site suffered many reverses; it was

leased for a time (1780‑86) to Anthony Bacon and was, afterwards, under

different ownerships until 1819, when it was acquired by William Crawshay I and

developed into an ironworks with four blast furnaces and a rolling mill, on the

left bank of the river Cynon, which took the works into the parish of Penderyn

and the county of Brecon. The ruins of four blast furnaces, a collapsed bridge

arch and other building remains, provide evidence of the disintegration which

happens over a long period of time ‑ the works was disposed of by the

Crawshays in 1864.

During one

of its thin periods, the sale of the works was considered and a list of

particulars was included in a printed document, drawn up for a proposed auction

sale in 1813, a copy of which, dated 26th January 1813, is in the Department of

Industry at the National Museum of Wales.

The

preservation of documents and papers relating to works, which have long ceased

to function, and to their technical contents, and to works which are

disappearing even currently after only a limited existence, is important in the

field of industrial archaeology. These documents often point to different

manufacturing techniques, and the rapidity of changes in these directions

emphasises the importance of such documents in recording industrial development

and progress.

The

Hirwaun document lists in detail the capital equipment and resources of a

medium‑sized ironworks in South Wales at the beginning o,f the nineteenth

century. Under Lot I it lists:

TWO

WELL CONSTRUCTED FURNACES

each

about 4o Feet high and of proportionable Diameter;

Two

Cast Houses, one about 45 Feet by 4o, and the other

36

by 33.

AN

AIR FURNACE, TWO FINERIESA CAPITAL BLAST ENGINE

On

BOLTON and WATT'S improved Principle,

now

Blowing the Two Furnaces and Two Fineries

with

78 Inch Blowing Tube and 38 Inch Steam Cylinder, working

a

6 Feet 8 Inch Stroke and Water Regulator.

A

FORGE

One

Hundred and Fifty‑Seven Feet in Length, 44 Feet in Width

at

one End, and 34 Feet at the other, with io Pudling

and

5 Ball Furnaces.

TREVITHICK'S

STEAM ENGINE

Working

by a 6 Feet Stroke, Two Pair of Pudling and One

Pair

of finish Rollers, capable of Rolling from

80

to 100 Tons Weekly.

Forge

Counting House, Pattern Room, Drying Sheds,

Carpenters'

and Smiths' Work Shops

Water

Wheel, Turning a Lathes for the Rollers, Grinding

Clay

&c.

Brick

Furnace Kiln, of sufficient Size to burn 13,000 common

Bricks.

FOUR

KILNS for CALCINING the IRON STONE,

Mineral Yard, Coke Banks, Two Counting Houses,

Three Lime Kilns, which supply Lime to the surrounding Neighbourhood to a

considerable annual Profit: and every Requisite for conducting the Business.

Under "The Mines of Iron Stone", it

says that:

"Several Veins of Ore of an excellent

quality, in various thicknesses, from 8j inches down to 3 inches, are worked by

Levels, the distance from the mouth or opening of the farthest does not exceed

23 miles from the Furnaces, and the nearest within 1200 yards.

"The Collieries comprise Four Levels,

called the Old Lime Kiln, Old and New Glovers and the Gothlyn. Having several

veins of Coal, some of good Coking Quality, other for the Furnace, in almost

inexhaustible supply, from 4 feet to 9 feet in thickness, these Levels are all

within Two Miles of the Works."

The need for meeting the housing needs of the

workers is reflected in frequent references to tenements; sixty‑four near

the works site, five at Penhow, thirty‑eight at Coedcafellin (quickset

hedge of mill), two (one unfinished) at Rhydia (fords) Mill, others at outlying

farms and in a reference to 'Two Pieces of Land part of Hirwain Common ... for

Building Houses for the Workmen near the Collieries.'

WEST GLAMORGAN,

CARMARTHENSHIRE AND PEMBROKESHIRE

At Neath

Abbey stand the ivy‑clad remains of two stone blast furnaces, which tower

above the ground. The original drawing of the furnaces has survived and has

been deposited at the Glamorgan County Record Office; it shows Number I furnace

to have been some 51-1/2 feet high from the furnace bottom and Number 2, 63-1/2

feet. In 1798 they were referred to as, ‘…Two immense blast furnaces belonging

to Messrs. Fox & Co. . . constantly at work, each of them producing upwards

of thirty tons of pig‑iron every week. They are blown by iron bellows,

worked by a double engine, constructed on the plan of Messrs. Boulton and

Watts, with a steam cylinder of forty inches in diameter.’117

The site

was leased in 1792 to the Cornish Quaker family, Fox, the names of Peter Price,

Samuel Tregelles and John Gould being also associated with the operation of the

ironworks in subsequent years.110 The firm's letters were variously

signed by the different partners102, their recipients often being

addressed 'Esteemed Friend', the letters ending, 'Your friends' or 'Thine

Truly'. The works remained under the management of the Quakers until 1875

In their 'engine Manufactory', this firm established for itself a very high reputation for the building of locomotives, stationary engines, marine engines and many kinds of machinery. It is very gratifying to be able to say that plans and drawings of these machines, numbering many hundreds, have been preserved and are available for study; they were deposited at the Glamorgan County Record Office in 1964 by Mr. A. W. Taylor of Taylor & Sons Ltd, Briton Ferry, Glamorgan.

There are,

still in existence, a number of examples of the finished work of the Neath

Abbey Works. In 1964 the Vivian Tinplate Works of the Briton Ferry Steel Co.

Ltd, were demolished; this works was established in 1926 on the site of the

Margam Copper Works. Parts of the roof structure of the building was supported

on two cast iron pillars, 16l inches in diameter, each bearing the date 1800

and the name 'N. Abbey'; a short length of one of these pillars including the

inscriptions is preserved in the Department of Industry, National Museum of

Wales.

Two further examples of Neath Abbey engines, which have survived, are to be seen at Glyn Pits, near Pontypool (ST 265999). One is a beam engine, together with pump, installed in 1845 in a building bearing the date and the initials C.H.L., Capel Hanbury Leigh, who inherited the industrial enterprises of Major John Hanbury of Pontypool. The other is a winding engine which drove two reel drums, each 15 feet in diameter, carrying flat winding ropes.

The

remains of the ironworks at Ystradgynlais (strand of Cynlais) and Ystalyfera

(water meadow at end of short share) are important because both works were

closely connected with developments in the technique