Garrett & Eastwick Locomotive Works

Later

Eastwick and Harrison

The third and smallest of the Philadelphia steam locomotive manufactures active in the 1830’s was Garrett & Eastwick. Although the smallest, it was perhaps the most innovative. The enterprise was begun in the spring of 1835 by Phillip C. Garrett and Andrew M. Eastwick with the specific goal of building an anthracite-fired steam locomotive. Garrett was originally a watchmaker who, in about 1830, engaged in the manufacture of steam engines. He was joined by Eastwick, background undocumented, who clearly had an aptitude for mechanical innovation. Although the enterprise continued in operation for but 15 years and produced only about 20 locomotives in America, the firm is noted for its many contributions to locomotive design. Both Garrett and Eatwick earned significant wealth and became prominent Philadelphians.

Up to that time, locomotives were fueled primarily by wood. No one had built a locomotive that could successfully utilize anthracite (stone coal) as that produced a myriad of problems including burned-out grates, insufficient or uncontrollable heat output, etc. (These issues are discussed in detail in later chapters.) The initiative was undertaken as a response to the newly-formed Beaver Meadow Railroad & Coal Co. request for an anthracite-fired locomotive and to the Lehigh Coal & Navigation company’s incentive to develop the same.

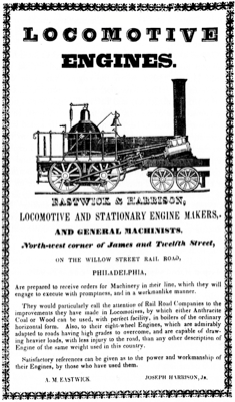

The company’s facilities were located on Wagner’s Alley, which, according to Scharf and Wescott were located “below Race Street”. (Not too far from Baldwin’s facility of 1834.) As can be seen in the following figure the location for Eastwick & Harrison is given as the northwest corner of James and 12th Sts.

Advertisement from an 1839 Philadelphia Directory.

Source John H.

White, Jr.

In order to staff their venture, Garrett and Eastwick attracted two men with backgrounds in the machinist trade – Hopkin Thomas and Joseph Harrison. Thomas came from Baldwin’s operation; Harrison had worked for Garrett who previously manufactured small lathes and presses for bank-note engravers. The two men had contrasting styles and capabilities. As we have seen, Thomas, 43 years of age, was highly experienced, trained at the renowned Neath Abbey Ironworks, inventive, modest and interested in the technology of the day – not in entrepreneurship. Joseph Harrison, 25, is said to have been in the machinist trade for ten years including two years at the Norris works, was somewhat egocentric, and ambitious. (In Harrison, 1839 became a partner with Eastwick -- at which time the company’s name was changed to Eastwick and Harrison.)

Hopkin Thomas Joseph Harrison

The experience and talent of these men and that of their employers was quickly put into practice. Within a year, the Journal of the Franklin Institute, which followed locomotive design developments closely, filed a report citing the following innovations which had been employed in Garrett & Eastwick engines in service or under construction:

a.) A means of reversing an engine by means of moveable valve seats operated by hand levers.

b. ) Improved axle, hub and wheel design which decreased axle wear.

c. ) An improved engine mounting method which added rigidity to the locomotive assembly.

How could so new a firm develop improvements at this pace? The answer most assuredly is that both Thomas and Harrison brought with them knowledge based on prior experience. Unfortunately we have no firm knowledge of the specifics of where this knowledge was acquired. Thomas, in all likelihood, had worked on locomotive design in Wales and was familiar with all the developments that took place in on locomotive development in Britain in the 1820 – 1830 time period. Harrison viewed his time spent at the Norris company as of a “negative character” when it came to professional education. Based on his Harrison’s assessment, it was probably the case that the two men adopted the British technology whenever the opportunity arose.

Hopkin Thomas’ stay with Garrett & Eastwick was brief as we shall see. Upon delivery of the first two engines to the Beaver Meadow R. R. in 1836, Thomas was offered the position of Master Mechanic (chief engineer) at the railroad’s facility in the town of Beaver Meadows, Pa. As noted above, Harrison continued at the locomotive works, where, after the slowdown associated with the Panic of 1837, he became a partner with Eastwick, then relocated the firm to Russia where great success was had, and finally Harrison became the principle founder of the Harrison Boiler Works in Philadelphia.

Joseph Harrison, proud of his accomplishments, published what amounted to an autobiography entitled The Locomotive Engine and Philadelphia’s Share in its Early Improvements. It is somewhat characteristic that Harrison does not mention the contributions of his early colleague, Hopkin Thomas. Harrison’s achievements were highlighted in an article appearing in Cassier’s magazine in 1910 as well as in Scharf & Wescott’s history, excerpted here.

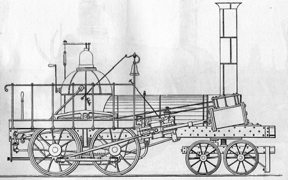

Perhaps the most significant of the contributions to locomotive design brought into practice by this firm was the suspension system that became known as “Harrison’s equalizers” in that it more evenly distributed the weight of the engine on the roughly aligned rails typical of American roadbeds. The earliest engine to employ the elements of such a suspension system was the Hercules, built in 1836.

Garrett & Eastwick’s Hercules, 1836

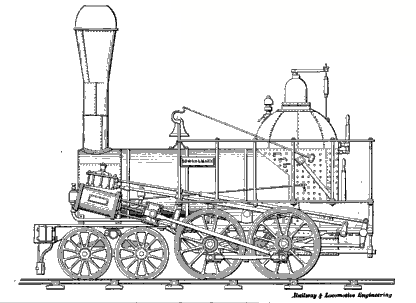

A later-built engine of 1839 that demonstrated the tractive capacity of a refined suspension system was the Gowan & Marx. At about the time the Gowan & Marx was being constructed, a committee was formed at the Franklin Institute to validate the claims of superior load-handling capability of trains headed by these locomotives. The Committee report was published in the American Railroad Journal in 1839. Included in that publication was a letter from Ario Pardee, of the Beaver Meadow and the Hazleton railroads which described the nature of the rails on which these engines were run. These engines and other pioneering locomotives are discussed by Angus Sinclair in his most thorough treatise on American locomotive design.

Eastwick & Harrison’s Gowan & Marx, 1839

Eastwick & Harrison took steps to ensure that the success of the Gowan and Marx was known to the railroading community – see the letter written to the editors of The American Railroad and Mechanics Journal in 1840. A further interesting sidelight with respect to this engine is an article that appeared in the publication Locomotive Engineering in 1893 to the effect that there was no known picture of this famous engine until the original drawing was discovered some fifty years after the engine was assembled.

A roster of the Garrett & Eastwick engines made in Philadelphia identifies 17 engines manufactured in Philadelphia. (The Nonpariel was built by Hopkin Thomas in the shops at Beaver Meadow, Pa. Some histories suggest that major components were acquired from Garrett & Eastwick.) Eastwick & Harrison moved their operations to Russia in 1843 where a large quantity of engines were built.

Return to the Table of

Contents

About

the Hopkin Thomas Project

Rev.November

2011.