The Anthracite Coal Industry

The development of the anthracite coal industry in eastern Pennsylvania led the way for the emergence of the anthracite iron industry and of steam-powered transportation. Each of these activities was key to the rapid industrialization of America in the mid-nineteenth century. Fuel in a compact and transportable form was the essential ingredient. The anthracite coal industry thrived for about 100 years and many a fortune was made. There have been many histories written – this brief account focuses on activities of interest to the Hopkin Thomas Story.

A Lump of Anthracite Coal – A Black Diamond

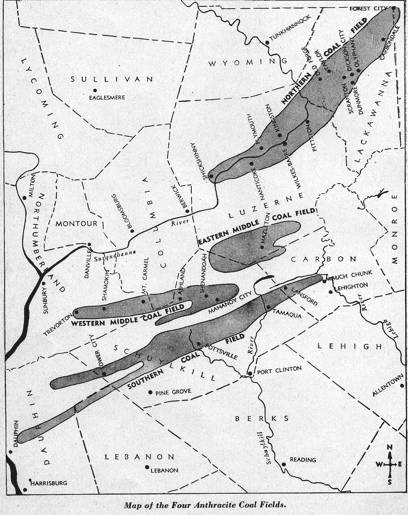

So exactly where were these coal fields? The map below shows that there were four principal fields in eastern Pennsylvania. Our story of Hopkin Thomas focuses first on the Eastern Middle Field as that was the location of the Beaver Meadow operations. Note that the Lehigh River is located at the lower right. Allentown is identified. It was along the Lehigh River north of Allentown where the anthracite iron furnaces were eventually located. The coal was transported from the mines to the furnaces by barges on the Lehigh in the early days. The Beaver Meadow mines were located on the eastern edge of the Middle field in Carbon County. Coal was transported by mule trains eastward to the Lehigh River where the coal was transferred to barges.

Click here for a detailed map of the Middle and Southern fields.

The second field of interest is the Southern Coal Field which extends eastward to Mauch Chunk on the Lehigh River. Mauch Chunk was the site of the famous Switchback Railroad. Coal was delivered by gravity from the mines to the ports at Mauch Chunk. Note that the town of Tamaqua, where Hopkin spent a number of years is located on the east branch of the Schuylkill River. The Lehigh and the Schuylkill rivers formed the major transport routes to the markets in Philadelphia.

Some details on the scope and depth of the coal fields can be found here.

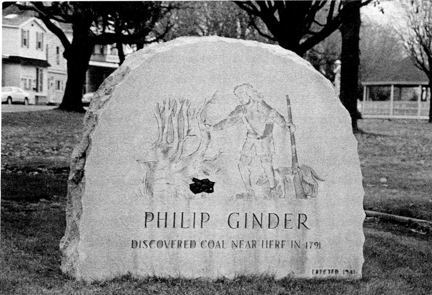

When were the coal fields discovered? There is a substantial amount of folklore regarding this subject. The existence of coal, or black stones, was apparently common knowledge among the first settlers in the region – the 18th century. But the credit for activities leading to the identification the substance is often given to a hunter/woodsman named Phillip Ginter whose cabin was located on Mauch Chunk Mountain. In about 1792 Ginter took a sample rock to Col. Jacob Weiss of Fort Allen who then took the sample to Philadelphia. After the sample was identified as anthracite coal, Weiss and others formed the ”Lehigh Coal Mine Company”. Their attempt to mine the coal and deliver it to the markets in Philadelphia failed due to the high cost of shipping and the fact that potential users of coal, like blacksmiths, found the substance would not burn. Anthracite coal quickly became known as “stone coal”. A concise account of Ginter’s discovery was published by the Carbon County Historical Society in 1914.

Monument to Phillip Ginder (Ginter) in Summit Hill,

Pa. Courtesy Knies, Coal

on the Lehigh

Actually, there is evidence that those living among the coal fields did, in fact, learn how to burn anthracite in their blacksmith forges – and, in fact, develop grates that eased the process of igniting the coal and developing a sustainable fire. In a letter dated 1826, Jesse Fell noted that blacksmiths in the Wilkesbarre area (located in the heart of the Northern Coal Field) had been using anthracite since about 1772 .(Note: Judge Jesse Fell appears in the Hopkin Thomas Family Ties chart as a member of the Giles Slocum Family.)

Over a period of a few years starting in 1792 the Lehigh Coal Mine Company delivered wagonloads of anthracite coal to Philadelphia and environs where various industrial concerns (many blacksmiths) attempted to use the fuel. A market never developed and the concern failed. Two lessons were learned from this endeavor:

Š Methodologies for easily burning anthracite had to be developed.

Š Costs of transportation had to be reduced significantly.

With respect to the burning of anthracite, the difficulty lies in the fact that anthracite is almost pure carbon – it does not contain a significant amount of hydrocarbons that become volatile at elevated temperatures. Bituminous and other soft coals give off these gaseous hydrocarbons when exposed to the heat generated by wood or other substances used in the ignition process. These hydrocarbons are easily ignited and the heat from this flame causes rapid pyrolysis (chemical breakdown) of the coal into carbonaceous substances which are easily consumed. On the other hand, anthracite oxidizes (burns) at its surface. The surface temperature must be very high for the oxidation process to occur. And oxygen (air) must be brought to the surface of the lump of coal. To complicate matters, the temperature of the combustion products is insufficient to maintain the surface temperature required due to the fact that the high temperature surface radiates much of the heat to the environs.

The solution to these issues was the use of a grate, upon which a layer of coal was spread, and the use of a furnace configuration that surrounded the burning coal. The burning coal creates a draft which is drawn through the grate so that oxygen reaches the coal. By use of a furnace enclosure, the heat loss by radiation is reduced and heat is re-radiated from the hot furnace walls back to the coal.

Stove designs capable of using anthracite for

residential heating and cooking were developed as anthracite became a readily

available commodity. Such stoves are available today. Many illustrations of antique stoves are available on the web.

It took well over a quarter century for these procedures to be employed by the various industries. As we shall see, finding solutions to these issues played a major role in the development of anthracite-fired blast furnaces and anthracite-fueled steam locomotives.

With respect to the issue of economical transportation, it was believed by a number of people that if the rivers – the Lehigh and the Schuylkill – could be tamed, this would be the solution. Nothing of substance was accomplished along this line until about 1813 when Josiah White and Erskine Hazard, Philadelphia entrepreneurs who ran a wire factory on the banks of the Schuylkill, developed an interest in the problem. White and Hazard had used anthracite in their furnaces and realized that anthracite could be the fuel of the future if the cost could be reduced.

White and Hazard decided to focus their attention on the Lehigh river – they eventually formed the Lehigh Coal and Navigation Co. which controlled both significant coal lands and the canal system built on the Lehigh. The story of how these men overcame all the hurdles that faced them is fascinating. A brief summary is available at the Switchback Railway web site, but the detailed account provided by M. S. Henry in his 1860 History of the Lehigh Valley reveals the true resolve that these men possessed. Perhaps the most succinct description of the task upon which they set out upon was that accompanying an act of the Pennsylvania legislature giving them the right to improve the Lehigh river bed. The act of 20th of March, 1818 was described as giving these gentlemen the opportunity of “ruining themselves."

An account of the early operations of the Lehigh

Coal and Navigation Company is also given in the History

of the Counties of Lehigh & Carbon by Matthews and Hungerford, 1884.

After 25 years of toil, the Lehigh Coal & Navigation Co. became a huge success. The extensive network of canals built throughout the coal country is shown here in a large scale map. The coal resources were plentiful and the transportation costs acceptable. At this point, White and Hazard undertook efforts to promote activities that would lead to the utilization of coal in major new industries. Today such endeavors would be sponsored by government agencies, but this was the era when entrepreneurs and capitalists, who had intimate knowledge of the subject, were in charge. Perhaps their greatest success was with respect to the usage of anthracite as the fuel in blast furnaces used to produce iron. In 1836, the Lehigh Coal and Navigation Company offered to any person who would establish a furnace, lay out thirty thousand dollars, and run successfully on anthracite coal exclusively for three months, the valuable water privileges extending from Hokendauqua to the Allentown dam. About that time, a Scotsman by the name of Nielson, discovered the process of using a “hot-blast” to promote the anthracite combustion process. In Wales, where the only other known anthracite coal fields were located, George Crane and David Thomas of the Ynescidwin Iron Works began experimenting with the process and succeeded in producing iron using anthracite. White and Hazard learned of this activity and Erskine Hazard traveled to Wales and induced Thomas to come to America and establish such a works on the Lehigh river. The result was the construction of The Crane Iron Works in Catasauqua on the banks of the Lehigh and the birth of the anthracite iron industry – a monumentally successful industry for over sixty years.

The activities conducted by the LC&N to initiate the anthracite iron industry are detailed in the Annual Report for 1839 in a section entitled Smelting Iron with Anthracite. It is pointed out that the Lehigh Crane Iron Company was incorporated in July of 1839 and the names stockholders, including White and Hazard, are listed. At the time of this writing, the minutes and annual reports of the Lehigh Crane Iron Co., which would contain details of the operations at the time that Hopkin Thomas was employed, have not been located. More on the Crane Iron Co. will be found on the section on The Anthracite Iron Industry.

LC&N also offered the powers of the Lehigh to other industries after the inception of the Crane – see an ad that appeared in the Mauch Chunk Courier in 1840.

A second activity that White and Erskine undertook was the promotion of the use of anthracite in steam engines – both railroad locomotives and steamboats. The 1838 annual report of the L C & N Co. contains the following:

The experience of Garrett & Eastwick, of

Philadelphia, in successfully using anthracite coal in their locomotive

engines, has received additional confirmation during the past year, on the

Columbia Railroad; also on the Sunbury branch of the Danville and Pottsville

Railroad, on which they have used no other fuel for several months past, in

drawing their coal. The Beaver Meadow company, and the Hazleton and Laurel H111

Coal companies, have their locomotives in use all burning anthracite coal

exclusively.

The notice regarding Garrett & Eastwick is, of course, of special note to us because of Hopkin Thomas’ involvement. In fact, it took many more years to develop all the techniques required to make anthracite attractive as a locomotive fuel. More on this may be found in the section on the Development of the American Steam Locomotive.

The above summarizes the events that made coal in the eastern-most fields a successful commercial product. Similar activities were being undertaken in the fields served by the Schuylkill River. This is of interest to us in that it helped promote the development of the town of Tamaqua where Hopkin spent some five years after his involvement with the Beaver Meadow Mining & R. R. Co. This topic is covered in a later chapter.

The anthracite coal industry went on from these early beginnings to become an enormously important and successful operation employing hundreds of thousands of miners, boatmen, railroad men, and laborers who emigrated to America - mostly from eastern Europe – the Slavic community. The industry thrived until after World War II (1945). During the following decade, pipelines were laid and residences all over the east coast switched from coal to either fuel oil of natural gas as a heating fuel. Locomotives switched to diesel engines from steam. The industry lingers on still today, but is more of a curiosity than a money-making proposition. There are many tourist attractions that are well-kept and worth a visit by the curious. Among those of special interest are:

Eckley Miner's Village, Weatherly, PA,. Eckley Miners' Village was an original anthracite mining town that is now a museum devoted to the everyday lives of the anthracite miners and their families. It is located nine miles east of Hazleton, Pa.

Pioneer Coal Mine Tunnel in Ashland is a very well-maintained museum which includes an actual tour of a coal mine shaft.

Centralia famous for the Centralia Mine Fire which is unique due to it's long duration (nearly half a century) and persistence. You can walk among the steam vents that pour from the fire not far below the surface.

Number 9 Mine and Museum in Lansford offers a coal mining museum and an underground mine tour.

Steamtown National Historic Site in Scranton is a working museum of steam railroading operated by the National Park Service, on the site of the old Lackawanna Railroad yards.

An auto tour of the coal patch towns is always interesting – some towns have made the conversion to a more modern economy and others look like no improvements have been made since the Great Depression. Be on the lookout for coal breakers – the last remaining monuments to a once great industry.

Many

coal breakers – monuments to an industry of yore – still dot the Pennsylvania

landscape.

There have been many books written on the history of the anthracite coal industry in Pennsylvania. Here a few used in this review:

Coal on the Lehigh by Michael Knies – describes the beginnings and growth of the industry in Carbon County.

Anthracite in the Lehigh Region by J. N. Hoffman contains the legislative act enabling White & Hazard to develop the Lehigh canal plus other interesting details.

The Story of Anthracite published by the Hudson Coal Company when the industry was flourishing – covers the business aspects of the industry including labor relations and management issues.

Buried Black Treasure by Carl Corlsen – focuses on several of the large coal towns – profusely illustrated.

Josiah White, Prince of Pioneers by Eleanor Morton – details of White’s LC&N activities plus information on his family.

Josiah White, Quaker Entrepreneur in the L. V. R. R. Guidebook– contains a collection of White’s correspondence.

Memoir of Josiah White by Richard Richardson – a history of his work on the anthracite coal and iron industries. PDF here.

The Death of a Great Company by W. Julian Parton – emphasis on company affairs in the 1930s and thereafter. The death notice may be a bit premature as the company is still operating and publishes a web site.

About

The Hopkin Thomas Project

Rev.

April 2015